All right, friends. I’m back with the second half of my 2015’s 6 FINAL READS.

I finally, after over a year, sat my ass down to finish reading this volume of the Young Miss Holmes manga series. And it was fantastic. I believe I stalled for so long because of the eight-part The Hound of Baskervilles case Christie investigated. Somewhere in the middle, I lost interest in the case. Only to find myself enthralled by it during my re-introduction.

But let me back up a little, for those who aren’t familiar with Kaoru Shintani’s Young Miss Holmes. It’s quite simple: ten-year-old Christie is the protege of her uncle, Sherlock Holmes. Endowed with his sense of chief intelligence (how theatrical of a description?) as her uncle, Christie spends her time running around England solving murder mysteries. And a variety of murders she encounters–almost freely. You see her parents are in India, so she’s aided by a pistol-toting maid named Ann Marie. Likewise, her servant, Nora, tags along on Christie's adventures. Though mostly unassuming, Nora stashed a forked tongue whip underneath her petticoats.

|

Ann Marie & Nora DON'T PLAY

when it comes to Christie! |

Christie’s curious and precocious nature aside, I find these characters bring much of the action and humor. I perk up whenever Anne Marie or Nora unleashes her respective attacks, in the face of protecting her charge. It’s equally entertaining watching Christie’s sneaky shenanigans and off-color comments aimed at her "protectorates." But don't get Christie wrong. She does bring her guardians trouble, both from her willful behavior and slick mouth. However, Christie cares deeply for the two. She's as protective and loyal to them as they are to her. And this is further shown in the two chapters dedicated to sharing the history of Nora and Ann Marie.

And it’s these two chapters I felt highlighted this volume. Nora’s chapter follows her life as a gypsy-slave, before finding solace under the care of Christie’s parents. As for Ann Marie’s story, we get a glimpse into her tragic childhood growing up in America. Shintani takes us all the way to post-Civil War Georgia, and on into the racial strife during the time. And you wouldn’t believe what he came up with. Then again, it may not come as a surprise given the context.

So the list goes for teenage sleuths:

1. Martha Grimes' pre-teen amateur sleuth, Emma Graham.

2. Alan Bradley’s sharp-thinking ten-year-old sleuth, Flavia de Luce

3. And Kaoru Shintani’s ten-year-old Crystal "Christie" Margaret Hope.

It's interesting how each series is historical–in a sense. Graham takes part in the 60s, whereas de Luce's a full decade ahead. As for Christie, she's a 19th century girl. And I can't wait to get into the third and final volume. I just love this kind of shit. Smart girls solving mysteries and kicking grown men ass! Or at least getting them locked up by the law.

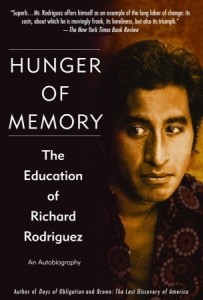

Here’s another book I wish to dedicate an entire blog post toward. But I’m sticking to my year-end wrap up here, as much as it pains me to hold back my thoughts. You see, I want to write more on the book for a variety of reasons. More so from the conversations generated by Rodriguez.

He uses a stream of socially-conscious and opinionated essays to piece together his autobiography. Some of his opinions may appear debatable, but I lean a little toward thought-provoking. I’ll break down the subjects he addresses later. But for the sake of holding myself back, I’ll drop a quick summary of the man.

Rodriguez’s Hunger of Memory recounts life as a Mexican-American living in Sacramento during the 60s to 80s. His story unfolds life as a child understanding a total of 50 English words. This leads him to a Roman Catholic school for his early education, where his teachers have concern for his inability to grasp English. Their suggestion is for his parents to speak more English around him, and so they do.

However, this early circumstance stirs the beginning of Rodriguez's life story. As a child, he begins to differentiate language and cultural differences between himself and his white classmates (as well as neighbors). Which language and culture was more acceptable? Which was correct for him? His questioning leads to trouble, and a doubtful perspective of his Mexican parents. Determined to control his future he learns to assimilate to American life. Of course via its academic system. This, in turn, causes Rodriguez to find himself distant from his Mexican roots. To further his troubles, he relays the strife he faces by not finding acceptance in the exchange. Instead of appearing as a successful middle-class American, he’s haunted by the “minority” label. A label he rejects as the use of affirmative action grants him professional opportunities. This troubles Rodriguez–and for obvious reasons. Still, he never manages to escape his label.

There’s plenty to consider from Rodriguez’s commentary, expressions, and opinions on his inner grapples. Or more so the Mexican heritage he bypassed in the divide between his aspirations. Furthermore, he takes apart his religion during the "Credo" essay. And I kind of recognized his salty view in that arena.

Nonetheless, it wasn’t until the final two essays that I truly woke to his voice. When he falls into the subject of his complexion and “minority” labels, I started to connect with his anguish. Though I smirked as well, seeing how he was the one who denied much of his heritage/culture in the chase for a middle-class "seat." Which he gained successfully, only to find himself alienated in the processes. The final essay on his profession ties up his story, and the isolating conclusion of his struggles. Closing the book comes his epilogue, featuring the silence he endures from his now disconnected parents.

Moving and kind of whiny in all the right areas, I have to give credit how Hunger of Memory drew me into the deep complexities of immigrant children struggling with assimilation and ambition. And I honestly have to say–I get it. Not one to toss aside my own background, I do understand what its like to ache for better. Or to long for a life beyond your parents' road. But like many things of that nature, it comes with a cost.

All right. All right. I can’t say too, too much about this book for a very important reason: I skipped toward the end. Don’t judge. Don’t laugh. Just hear me out when I say I started the book in the spring of 2014 and only now decided to finish it up. Now I managed to get through 100 pages–back then. And the book is only 240-or-so pages. So I figured my new, determined and focused attitude would sail me right through this. Besides, I enjoyed James’ first Dalgliesh book enough to come this far. With the expectation of moving further into the series. So I came pumped and ready to go. Then almost instantaneously, I got that familiar dry and dull buzz from over a year ago. James is so meticulous of a crime fiction writer that I found myself soaked too deep into her time frames and mathematics. I say that as opposed to her crime and character. So. I skimmed lightly toward the final 40 pages and tread on to the finish line. And that’s just the way the damn cookie crumbles. Judge those who may, but after a year, I consider this a FINISHED READ.

With the intentions of getting the third book somewhere in the unforeseen future. Cross all fingers.

Nonetheless, since I’m finished whining, I’ll “remind” everyone what happens in this books.

Via Goodreads!

BHAM…

"On the surface, the Steen Psychiatric Clinic is one of the most reputable institutions in London. But when the administrative head is found dead with a chisel in her heart, that distinguished facade begins to crumble as the truth emerges. Superintendent Adam Dalgliesh of Scotland Yard is called in to investigate and quickly finds himself caught in a whirlwind of psychiatry, drugs, and deceit. Now he must analyze the deep-seated anxieties and thwarted desires of patients and staff alike to determine which of their unresolved conflicts has resulted in murder and stop a cunning killer before the next blow."

And that's it my friends! My 6 FINAL READS of 2015. But remember to please leave your comments on your 6 FINAL READS OF 2015 down below. I'm currently powering my way through Haruki Murakami's monster, 1Q84. I'm tackling this one a year later, with the intent of going after my large books this year. And there are plenty to keep me company.

In case this is the last post before New Years: HAPPY NEW YEAR, EVERYONE! Keep READING, DRAWING, AND LIFE'ING.

Wait. I think I have another post in me.