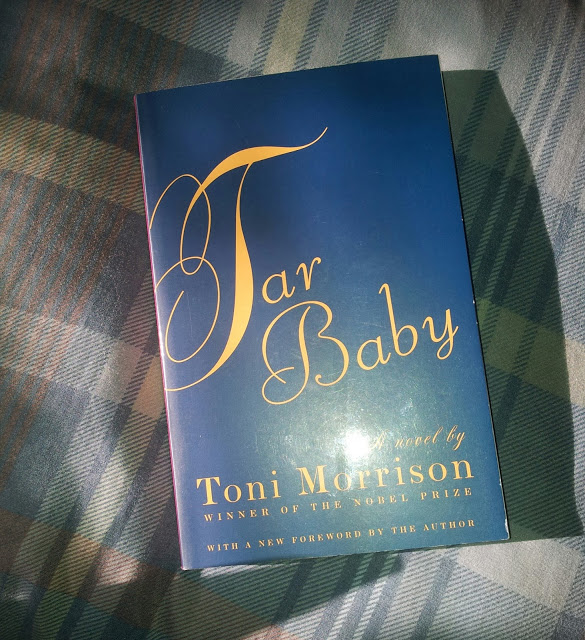

Toni Morrison’s Tar Baby was an amazing book. However, I first must admit that it took me about 150 pages before I finally, finally really got into the book. After that it took me a single day to swallow it down with a satisfying gulp. I also can’t believe it took me years to even get the book, after having read many of her novels with finger-licking happiness. I read a range of books by different authors of different ethnic backgrounds, but I love Morrison’s books mostly because I love reading about black people, or in essence, people sharper in my range of background familiarity and social positioning. People who think and have the same thoughts and anxieties as I. People that devise recipes and share folkloric stories that heed about the tragedies of being black in America. I find much of that and more resonating without a whimper in Morrison's stories, therefore she has always been a clear choice on days when I want to explore these kernels of meaning.

Now, I must add that I am much more of a Toni Morrison fan pre her Jazz novel. Though I enjoy her novels (as we know now) she is not always easy to read. Sometimes it takes a minute to get into the gears of her novels, but once there it's a gently rocking sailboat ride to the end. However, something about her works from the 90’s forward takes a little more work for me to find the coherency between her poetic syntax of her storytelling. A Mercy is one example where I opened the book and had no idea where the hell I was and was going because of the overload of poetic passages. Sometimes, I just need a character in a setting saying what he/she has to say to another to get me loaded and invested.

But I digress...

I wanted to write this blog not to get into a review of Tar Baby, because it would be terrible for me to start book reviews with material by someone as complex a writer as Toni Morrison. Besides, who am I to review books when I read them for emotion. I really just wanted to express my rounding thoughts about what the book left me with. As well as how I reverberated (though it took me a minute) with Jadine Childs’ point of view toward the end of one of the material's many disputes against disowning your race and so on.

Now, there are a thousand reviews and analysis on the book, especially considering its initial 1981 release (two years before I was born). So people have already spoken about the gender role complexities of the novel. Not to mention the civil/uncivil race relations between blacks and whites. Entitlements and suffering. The haves and have nots. Themes in the novel range from removing and finding one’s African roots. As well as incorporating into white society; necessary or not for an affluent lifestyle? Definitions of beauty and acceptance are also thrown in the thematic mix, and so much more in your classic Toni Morrison eye-opening fashion. So it's all been picked over in peer essays and research papers across the globe. Why even attempt to do any more?

However, I just want to talk about what I walked away from the novel feeling, because the closer I got to the end, the more I felt like I had to choose sides between the two main characters: Jadine and Son.

Tar Baby’s main character is a motherless woman named Jadine Childs. She is an African-American fashion model who spends much of the novel in the Caribbean where her aunt and uncle work as the help to two wealthy Caucasian individuals (husband and wife) with their own, dark back-story that unfolds throughout the novel. Nonetheless, these wealthy individuals provided Jadine with an education throughout her years, as well as a pedigree of sorts. With this upbringing, and her strong interest in art, Jadine aspires to own her own business and continue to explore the world with a near privileged perspective of her life removed from her black roots.

Then there is a fugitive named, Son. Son is an African-American man who comes from the South. He’s on the run after finding his wife in bed with a teenage boy, thus driving his car through the house killing his wife whereas the boy lived. So in the proceeding off-stage events, Son becomes a stowaway on a boat that makes its way to the Caribbean, eventually finding himself in the presence of Jadine and her white patrons. Morrison reveals much of Son’s tired journey from a lurker of the wealthy Caribbean-dwelling family, to an intruder, then eventually to a prized guest (exclusively to the patriarch) of the family. With this Morrison sets the stage for the dynamics between Son and Jadine as they both began to butt heads concerning ethnic responsibilities as well as tango with their desire for one another.

Not to spoil or give away much of the book, but the story leads us readers to Manhattan where Son and Jadine began their sort of committed courtship with one another. During this period Jadine is constantly nudging Son to go to college and find himself a real job--a career. She also shares ideas of traveling and starting a business together with him. This nudging spoke to me that Jadine wanted to "save" Son's future with a “proper” education, and being aware of his Southern background, save his cultural outlook as well. To Jadine, this can be done with financial assistance from her own white patron and somewhat friend to Son. This white patron is, of course, the patriarch from the wealthy Caribbean family the two left to purse life in New York. So while Jadine is falling in love with Son, she, quiet frankly, looks down on him. Or better yet, she can't get pass certain aspects that make up his mentality and directions with life. However, the same can be said from Son’s perspective of her. Here, Son wants to "save" Jadine from what he perceives is her sort of “whitewashed” world of thinking, believing that Jadine should stop trying to fit into that world and accept that she is not only black, but not as privileged as she believes.

This is where I started to understand the novel, even in regards to the many other elements happening between Son and Jadine as well as the other characters. I started to feel like I was suppose to pick a side between Jadine or Son. Do I take root in one concept over the other? Or is there a gray area?

When Son took Jadine to this hometown in the South, Eloe, did I sympathize with Jadine’s point-of-view because it beat against something inside of me on an idiosyncratic level. In Eloe, Jadine was introduced to women and men who more or less “represented” the sort of dominated position that African-American’s faced in America. In retrospect I see that the visit was going to be too much for Jadine when her first words upon entering the town was: “This is a town… It looks like a block. A city block. In Queens” (244). Eloe is too small for Jadine. It is too narrow. Yet… recognizably familiar, or not too distant for her fancy sensibilities. Now, that doesn't mean she put on airs about entering Eloe, she just knew that despite her reluctance, there will be a way out of there. Therefore, Jadine was willing to continue along with the journey. However, the more Jadine explores and confronts what she sees in Eloe, the more she is ready to take Son (her lover and "prodigy") and escape. It is particularly the women of Eloe that causes Jadine to panic, so much so that she sees the “spirits,” or reflections, of these women within the people of Eloe. The passage I favored in my decision to become somewhat Team Jadine reads:

“The women had looked awful to her: onion heels, potbellies, hair surrendered to rags and braids. And the breasts they thrust at her like weapons were soft, loose bags closed at the tips with a brunette eye. Then the slithery black arm of the woman in yellow, stretching twelve feet, fifteen, toward her and the fingers that fingered eggs. It hurt, and part of the hurt was in having the vision at all--at being the helpless victim of a dream that chose you. Some was the frontal sorrow of being publicly humiliated by those you had loved or thought kindly toward. A little bitty hurt that was always gleaming when you looked at it. So you covered it over with a lid until the next time. But most of the hurt was dread. The night women were not merely against her (and her alone--not him), not merely looking superior over their sagging breasts and folded stomachs, they seemed somehow in agreement with each other about her, and were all out to get her, tie her, bind her. Grab the person she had worked hard to become and choke it off with their soft loose tits.” (262)

Beyond the amazingly poetic syntax, this passage is amazing to me because Morrison caused me--the reader--to feel the swell of panic inside of her character, Jadine. This is where I began to realize that I was in fear of Jadine just as well as myself. Now, I most certainly do not have the prestigious background that a character such as Jadine has. No white man directly took care of my educational and cultural needs. I didn’t grow up with a silver spoon, and I am from and currently remain in my home city in the South. Which isn‘t so bad only that I know my potential lies in other cities and countries just as I dreamt to be free to explore them with my talents. However, I know what it’s like to see your surroundings and fear that you will become and remain one with it, even if you are proud of where you come from. So in that respect I acknowledge that I am different than the character of Jadine, and we certainly don’t see/view our race and others the same.

However, her anxiety at seeing the women of Eloe translated within me my anxiety of being stuck in my own surroundings. And I believe this sort of anxiety applies to anyone with racial circumstances far removed.

When Jadine asked for better out of Son I felt both her urgency and a reemerging of feeling for someone to ask for better out of myself. Other readers may see it differently and disagree. Maybe see it from a layer so conceptual and complex that even I might change my mind. But I still felt and understood Jadine’s desires because I grew up feeling pieces of that way. I mean, let's be honest. It didn't mean I wanted to run and disown my background, it just meant I wanted to stretch myself as an individual. My biggest fear in life is not necessarily snakes, rats, or even being murdered on the streets, while they all are fear inducing. No, my biggest fear is failure to reach my potential. Now, with all of the self-help and inner work I’ve been doing, I’ve learned to accept that there is no such thing as such. That life always gives us what we need. That our thoughts are things and therefore it is important to think and speak in an enlightening and positive manner.

So I am in no way siding with Morrison's purpose for Jadine to disregard one's cultural background. But I do know that tension, that panic, that swell of anxiety that comes across me when I want so much more for my life and the people surrounding me. When I look at my surroundings and all the things I don't particularly want and believe is "right" for me, I pray for me to recognize that I deserve more and to realize how to find such for myself. Maybe the one thing I believe Jadine doesn't know that I know is what it is like to scream day-after-day for the opportunity to simply shine, feeling as if no one prepared or groomed me to do it so it comes from within in another form.

At the end of the day, I just want this blog post to express how I know what it's like to want to escape. To want more for yourself than what is immediately before you even if it is a part of you and your make up as a person, but not necessarily an individual.

Morrison, Toni. Tar Baby. New York: Vintage International, 2004. Print.